On an x-ray, the density of the area influences the colour seen.

Denser areas, such as bone, appear as white. Air filled areas appear as black. Muscle, fat and fluid will appear in shades of grey, becoming lighter the denser the area is.

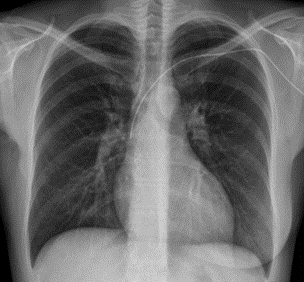

The picture on the left is a normal, healthy chest x ray (CXR). The lung fields appear dark, with no signs of consolidation or effusion, the heart appears a normal size, the trachea is midline and clear outlines of the ribs, clavicles, trachea, heart, and hemidiaphragms can be seen. This is a good chest x ray!

Unfortunately, in ICU, they don't always look this lovely (and not just because the chest is covered in leads and stickies that make trying to see anything nearly impossible) due to the presence of respiratory pathology and lines, tubes and devices.

Images taken from google searches unless otherwise specified.

The advantages of CXR include being non-invasive, painless, low risk and quick. There is the ability carry it out at the bedside with rapid results that are relatively easily interpreted.

There is a small risk of developing cancer many years later due to the radiation exposure- for a chest x-ray, the risk of cancer development is cited as 1 in 1,000,000 as the radiation is equivalent to several days worth of background radiation exposure. The risk does increase slightly with repeated exposure and in pregnancy.

Brief terminology (because I'm lazy and don't like writing out full words)-

CXR- chest x ray

RLL- right lower lobe

LLL- left lower lobe

ARDS- acute respiratory distress syndrome

COPD- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

IJ- internal jugular (vein)

SC- subclavian (vein)

The view for a CXR will be PA (posteroanterior- form back to front) or AP (anteroposterior- from front to back). Most commonly for ICU patients who are having a portable CXR an AP view will be used as this doesn't require the patient to be standing up. The image should be captured at the peak of inspiration to allow for maximum chest expansion and the best view of any respiratory abnormalities.

Our physiotherapists (who know literally everything about chests that you would ever need to know) taught us an ABCDE assessment method to quickly scan a chest x-ray. As a nurse, you're not necessarily expected to know much about reading x-rays, but its nice to know roughly what's normal, and be able to identify any big issues quickly.

ABCDE for reading CXR...

Airway-

Is the trachea central? Deviation indicates an unequal pressure in the chest cavity, which leads the trachea to shift towards (in lobar collapse- lower pressure) or away from (in tension pneumothorax or large pleural effusion- higher pressure) the lesion.

Are there any obvious signs of narrowing? This could indicate stenosis or oedema.

Where is the carina? Usually lies between T4-T6

Bones-

Assess ribs, clavicles, scapulae, and vertebrae- any evidence of fractures or lesions?

Assess intercostal spaces (the gaps between ribs)- are the symmetrical? Do they look widened? This can indicate hyperinflation of the lungs.

How many ribs are seen on each side? Can usually see 6-8. >8 can indicate hyperinflation, <5 can indicate underinflation (aim to take X-ray at peak of inspiration)

Cardiac-

Cardiothoracic ratio- the widest point of the heart compared to the widest point of the chest cavity, The heart should be around 50% of the size of thorax, with approx. 2/3 of the heart on the L side, and 1/3 on the R.

Images taken AP view can have the impression of a larger heart when compared to PA views This could lead to an inaccurate impression of cardiomegaly.

Are the mediastinum borders clear? Does the mediastinum appear enlarged? This could indicate an aortic aneurysm.

Diaphragm-

The right hemidiaphragm will sit up to 3cm higher than the left due to the location of the liver.

Are the borders of the diaphragm smooth?

Diaphragmatic elevation can indicate abdominal distension or atelectasis. Diaphragmatic depression can be seen in COPD patients and in pneumothorax.

Everything else-

Are lung fields equal?

Any areas of consolidation?

Are lung edges well defined? Pneumothorax, haemothorax and pleural effusion can all distort borders.

Look for lines, tubes and devices (see below!)

Also worth mentioning that breasts will appear on an x-ray. Don't do what I did when looking at my own x-ray and assume there are some terrible dense masses sitting on your diaphragm, because I forgot that boobs existed for a minute.

A CXR can be used to assess someone's respiratory pathophysiology and see the extent of a condition. The x-rays below show ARDS vs pleural effusion vs RLL pneumonia, and later a L sided pneumothorax and L sided tension pneumothorax.

ARDS is a rapid onset inflammatory response, that forms part of SIRS that is often seen following trauma, severe pancreatitis, burns or infection (including sepsis and COVID-19). There is widespread, diffuse interstitial and pulmonary oedema, which leads to a hazy appearance on CXR with 'ground glass' changes across all lung fields, alveolar damage, and a loss of aerated lung tissue.

ARDS can be diagnosed following CXR and after cardiogenic causes of pulmonary oedema have been ruled out (e.g. cardiac failure, fluid overload). Treatment includes oxygen therapy alongside mechanical ventilation using lung-protective mechanisms (see this post for further information following the famous ARDSnet trial) and recruitment manoeuvres to increase useable lung volume and reduce V/Q mismatch.

Pleural effusion is a collection of fluid in between the layers of the pleura, surrounding the lungs. Around 20% have no identifiable cause, but possible causes include cardiac failure, hypoalbuminemia, malignancy and pneumonia. Chest expansion and breath sounds will be reduced on the affected side, and in massive effusion the trachea may deviate away from the affected side. The CXR shows white, dense fluid in the lower lobes which can be treated with thoracentesis (needle aspiration), pleurodesis (injection of an irritant) or tube thoracotomy (chest drain insertion). Similar conditions include empyema and haemothorax- the only real difference being the type of fluid accumulating.

Pneumonia is a prevalent condition in ICU, both as a cause of admission, and as a potential consequence of treatment, as a ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP- this can be reduced by following the VAP care bundle, see this post). Clinical signs include reduced expansion, percussion dullness, bronchial breath sounds and added crackles. The appearance of the CXR is similar to that of ARDS, but the opacifications are denser and more concentrated to specific lobes (to the RLL in the above CXR). Treatment mainstays are supportive care (supplemental O2, fluid and electrolyte optimisation etc) and targeted antimicrobial therapy if appropriate.

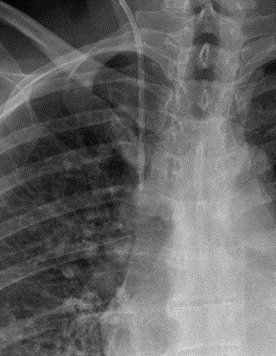

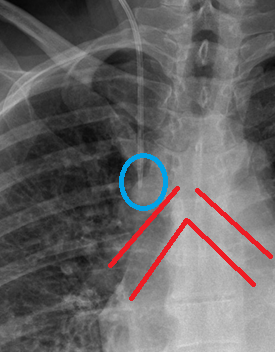

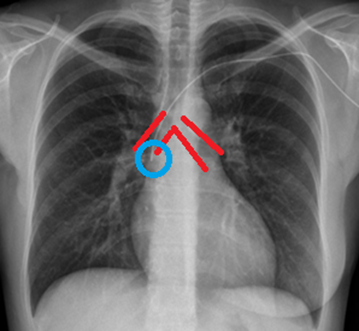

These CXRs show 2 types of pneumothorax- a standard L sided pneumothorax, and a L sided tension pneumothorax with tracheal deviation and mediastinal shift.

A pneumothorax is a collection of air in the pleural space around the lung (hence the dark appearance on CXR near the LLL), and can be classed as spontaneous, iatrogenic or traumatic. Clinical manifestations include subcutaneous emphysema, reduced expansion and breath sounds, with hyper-resonance on percussion. In massive pneumothorax, trachea will deviate away., and also...

In a tension pneumothorax, there is an element of communication between the lung and the pleural space- this allows air to enter the pleural space on inspiration, but does not allow it to exit on expiration. This leads to a build up of air and pressure, causing displacement of the mediastinum, compression of blood vessels (so reduced cardiac output) and impaired ventilation (so hypoxaemia). In the above CXR, the pressure form air around the L base is shifting the trachea and mediastinum over towards the R side.

Treatment for any pneumothorax relies on removing the air to relieve pressure- so needle thoracostomy (The Resus Room podcast has an interesting discussion around needle decompression, and the impact of chest wall thickness and location of needle insertion on success of this- 12 March 2016, linked below) and ongoing management with a chest drain.

In severe cases of pleural effusion, atelectasis (with collapse of an entire lung) or consolidation, the CXR can show what's known as a 'white out'. Which kind of does what it says on the tin- one hemithorax is entirely white, and as expected, ventilation will be affected. Diagnosis of the cause of a white out will depend on other clinical signs- does the trachea shift towards (in lobar collapse) or away (in pleural effusion)? What does the chest sound like on percussion or auscultation?

CXR is also used in ICU to confirm the positions of medical devices- notably, the endotracheal tube (ETT), nasogastric tube (NGT) and central venous catheter (CVC). Again, as a nurse you wouldn't be responsible for reporting on and confirming the position of these tubes, but it's good to know roughly what you're looking out for, to connect the theory and practice. In all the following scans, I have included a blank version alongside a version with landmarks and markers drawn on.

ETT

The ETT should be in the trachea (confirmed with auscultation, presence of bilateral chest expansion and gold-standard capnography- as per NAP4 findings) with the tip sitting approximately 4cm above the carina- the point where the trachea bifurcates, to ensure that both lungs are being ventilated. The ETT will have a blue line down the centre- this is a radio-opaque line which allows the tube to be seen on x-ray, and this line should be midline in the trachea.

If the tubs is advanced too far, it is more likely to be sitting in the R main bronchus as the R is more vertical, shorter and wider compared to the L main bronchus. If only one lung is ventilated, the other is likely to collapse, and this is bad. An ETT requiring withdrawal, indicated by unilateral chest movement and air entry, and inadequate ventilation + hypoxia, is an airway emergency, and ideally the person who inserted the tube should be responsible for withdrawing it under direct visualisation.

NG

Not every NG tube needs to have the position confirmed radiologically. The majority of NGs in a hospital will be confirmed using pH testing, but high risk patients will also require x-ray confirmation- most ICU patients will be classified as 'high risk'. High risk includes patients undergoing mechanical ventilation or NIV, who are 65y/o+ and those who are confused or delirious,

NG tubes will either have a radio-opaque strip down them, or have a radio-opaque guidewire that must be kept in until position is confirmed (you technically won't be able to remove the guidewire until it's confirmed as it requires flushing the tube, and you can't flush until it's confirmed). The body of the tube should be seen centrally down the mediastinum and crossing the diaphragm in the midline.

The tip of the tube is also radio-opaque, and should be seen in the stomach below the level of the diaphragm.

These x-rays show NGTs in incorrect positions- the L demonstrates that the tip has not yet crossed the diaphragm, so is not in the stomach and therefore needs to be advanced further. The R image shows that the body of the tube is not running midline through the oseophagus, but instead deviates down the trachea to the left with the tip sitting at the base of the L lung

CVC

This image is taken from Radiology Masterclass with their annotations included- thank you!

The tip of the CVC should sit in the bottom 1/3rd of the superior vena cava (SVC), just above the right atrium (RA). It is difficult to visualise these vessel and cardiac structures on CXR, but the locations can be approximated by identifying the carina and borders of the heart.

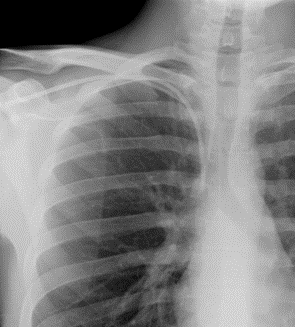

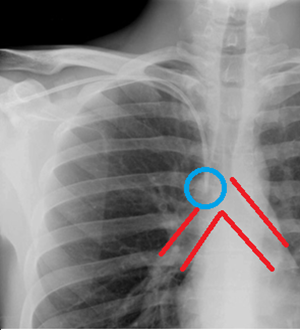

The angle and direction of the CVC will depend on which side and vessel is being catheterised- the images below show a RIJ, RSC and LSC line. The tip of each line is circled, and the bifurcation at the carina highlighted.

The line inserted into the RIJ is oriented vertically, going over the clavicle. In contrast, the RSC sits more horizontally under the clavicle but the distal tip still sits vertically in the vessel.

Similarly, the LSC line enters horizontally under the clavicle but again, the distal tip sits vertically in the SVC. Because of the shallow angle in the LSC, the tip sits further past the carina than the other 2 lines- this is to prevent the tip from touching the SVC wall and causing vessel erosion by enabling a more vertical placement of the tip.

It can be difficult to identify structures, and in particular to identify lines on CXR so practice really is key. It's worth having a look at some 'normal' x-rays to get confident in normal anatomy, which will make identifying abnormal pathology easier. Speak to your doctors for guidance or tips, and absolutely speak to your physiotherapists for wisdom about anything to do with chests- they really do know best!

Thank you for reading all the way through this post! I really hope you learnt something useful that you can take into practice with you. Below is a list of sources and resources, and I've bolded the ones that I think are most useful or that influenced most of this post!

Please like and comment on this post or on twitter/instagram (@christienursing) with any questions/suggestions, and feel free to share!

Love, Christie x

Sources...

BACCN (2020) Espresso Education webinar by Dr Mark Tehan

Critical Care Practitioner (2019) 'Chest X-ray'. https://www.criticalcarepractitioner.co.uk/core-radiology/chest-x-ray/

Lloyd-Jones, G. (2019) 'Chest X-Ray- Tubes- CV Catheters- Position'. https://www.radiologymasterclass.co.uk/tutorials/chest/chest_tubes/chest_xray_central_line_anatomy

Pezzotti, W. (2014) 'Chest X-ray interpretation: Not just black and white' in Nursing2014. 44(1), pp. 40-47

The Royal College of Anaesthetists and The Difficult Airway Society (2011) 'National Audit Project 4- Major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom. Report and Findings'. https://www.nationalauditprojects.org.uk/downloads/NAP4%20Full%20Report.pdf

The NAP4 report is a touch over 200 pages long, but is actually a fantastically interesting read. Each year the audit focuses on a different aspect of airway and anaesthesia based off reported incidents and emergencies from hospitals across the UK, to facilitate learning from these. Key findings in NAP4 include use of capnography, intra and post-op airway management, including in ICU, aspiration with artificial airways and tracheostomy care.

Oxford Medical Education- 'Causes of tracheal deviation'. http://www.oxfordmedicaleducation.com/clinical-examinations/respiratory-examination/causes-tracheal-deviation/

Baid, H., Creed, F., Hargreaves, J. (2016) Oxford Handbook of Critical Care Nursing, 2nd edn.

A great resource for pathophysiology of specific respiratory conditions, gives a concise and clear overview of signs and symptoms, diagnosis and management.

The Resus Room (2016) - Needle Thoracostomy (podcast). www.theresusroom.co.uk/needle-thoracostomy/

Simon (quite possibly the love of my life) discusses evidence surrounding needle thoracostomy for pneumothorax with Dr Zaf Qasim. Factors considered in successful decompression include chest wall thickness and location (2nd ICS, midclavicular vs 5th ICS, anterior axillary).

Radiopaedia- 'Tension pneumothorax' https://radiopaedia.org/cases/tension-pneumothorax-30

Karkhanis, V., Joshi, J. (2012) 'Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment and management' in Open Access Emergency Medicine. 4, pp. 31-52

GP Notebook (2018) 'Types of pneumothorax' https://gpnotebook.com/simplepage.cfm?ID=-1476001780&linkID=26830&cook=no&mentor=1

Drury, N., Moro, C., Cartwright, N., Ali, A., Nashef, S. (2010) 'A unilateral whiteout: when not to insert a chest drain' in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 103(1), pp.31-33.

Comments